As we sit at home, with the pews empty, wondering when life will return to normal, it is worth reflecting that Saint Mary’s has seen over one thousand years of trials, tribulations, joys and disasters, for the parish of Storrington.

Invading Normans, the Black Death, the persecutions of the Reformation, the Plague, Civil War, The Great War, Spanish Flu, and WW II, all have interrupted the daily routine of our church.

And this is not the first time we have been denied entry to hold services. In 1745 the tower collapsed, bringing down the Nave roof, and services had to be held outside for a while.

Many of you will be familiar with the history of our church, but for the rest of us, a quick canter through our updated historical guide may prove an interesting diversion from the deprivations of self-isolation.

A brief guide to our lovely church

Our church has undergone many changes over the centuries, and we are still making changes today, to keep us fit for purpose in the 21st century, whilst admiring and respecting the sanctity of our building and the craftsmen’s skill.

The current restrictions have seen the church enter a phase with a more digital presence, out of necessity, but probably here to stay in some part. We have also been reminded that a church is founded more on people than on stone.

Nevertheless, we have a great affection for our lovely church building, and a familiarity with its many memorials and features. Here is a guide to the history behind some of these.

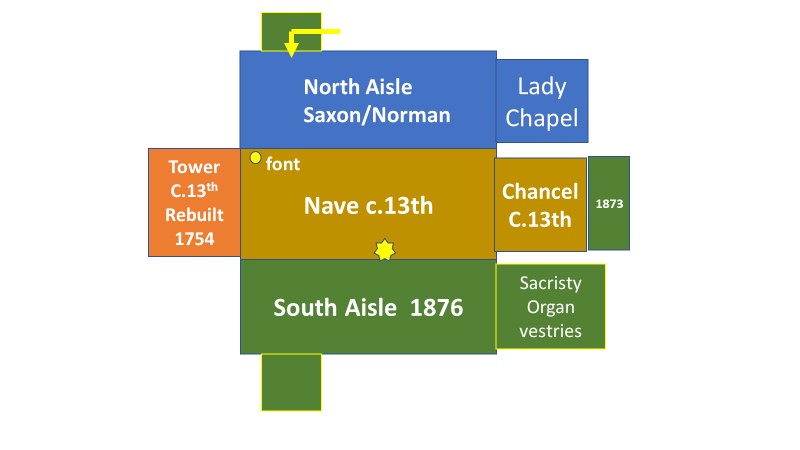

The present North Aisle and Lady Chapel (then the Chancel ) are believed to date back to between 700 and 1000 AD, with a Norman Church recorded in 1086 in the Domesday Book.

Since then, the original small North windows and original entrances have been closed up, but if you look carefully, you may still see where some of these were. The church was significantly enlarged in the 13th century, when the Nave and its Chancel, and a West Tower were built. The tower had a fine high spire, but a lightning strike in 1732 meant it had to be rebuilt. Sadly, this was not a quality repair, and in 1745 the tower collapsed, bringing down a large part of the Nave roof. History records that the 15 souls inside at the time escaped unscathed, but it was 9 years before funds were raised for a more durable rebuilding.

As was the fashion of the times, three private galleries were then erected over the pews of the North Aisle, and a small gallery at the West end, where notable local families could worship from an aloft position. In 1842 these were replaced with a single gallery, which lasted until the 1870s

When the Rev, George Faithfull commissioned the enlargement of the church in the 1870s, the font was in the centre of the church, and the pulpit on the south wall (marked with a yellow star on the plan) with all the pews and galleries looking at the Preacher, not the Altar.

Rev. Faithfull re-orientated the church to its current layout. He built a new South aisle, supported by pillars of local Pulborough stone to match the 13thcentury pillars to the North Aisle, extended the Chancel East wall by 9 feet, and built porches and the pitched-roof vestry. But he didn’t stop there. The roof of the Chancel was raised, and a new Chancel Arch erected (the old one being recycled into the South wall of the Chancel). He brought in the Oregon pine pews that we still sit in today, and replaced the Font with a new Victorian one in the current position ( some 50 years later the old Font was found in nearby Cootham and restored to St Mary’s. It is believed the Victorian Font is now in Henfield church).

The Rev. Faithfull was not the only Victorian vicar to make alterations. In 1811- 1857 the Rev. William Bradford was Rector at St. Mary’s, and he undertook some alterations to the Tower and Nave 1n 1842, but these were not the biggest impression the Rev. Bradford left on our church. In the alterations to the Chancel wall in 1873 the magnificent window was installed as a memorial to his William Bradford and his wife, Martha. These were unusual characters for a country parson and his wife, and not only did they lead colourful lives, but their extended relations account for most of the larger memorials in the church.

William Bradford’s older brother was on Wellington’s staff in the Peninsular war, and got William a job as brigade chaplain, where he served in Corunna, to return to become the Rector at Storrington. In 1819 he took a second job, as Queen Victoria’s chaplain to the British Embassy in Vienna, and spent ten years amid the gaiety of Viennese Society, whilst his curate looked after the parish here, until the Rev. Braford and Martha returned to their quiet life in charge of St. Mary’s.

Continental high-life may not have been the shock for Martha we might expect, as she was born (in Ireland) of an old English family and had spent 5 years in Russia as companian to a Russian Princess, in furs and fine carriages.

Jane Falconer was neice to Rev. Bradford, and she lived many years in Storrington. Her memorial is a pair of Lancet windows in the South Aisle. There is also a memorial tablet over the north door for her father, mother, and sister.

Isabella Dalzell, Countess of Carnwath, was neice to Martha Bradford, and there are fine memorial tablets in the Lady Chapel for notable members of the Dalzell family (pronounced Dee-ell), some sculpted by Sir Richard Westmanctt junior 1799-1872, who, like his father, Sir Richard Westmancott snr., was Professor of Sculpture at the Royal Academy. The father executed the memorials to Sir Henry Hollis Bradford (William’s younger brother) and major Hugh Falconer ( William’s brother-in-law) over the south and north doors.

Other notable features in the church include the memorial east window in the Lady Chapel, dedicated to a leading local storekeeper, James Constable, installed as part of the Rev. Faithfull’s alterations and depicting Christ on the cross, looking down at Mary Magdalene and watched by his mother, Mary, and St. John. In more modern times (1931) the circular window representing St. Dunstan, Patron saint of blacksmiths and complete with fire and anvil, was installed in the Tower at the same time the Chancel Arch was reconstructed. Not all the memorials date from Georgian times onward, and in the Chancel is a brass commerating Henry Wilsha, Rector between 1551 and 1592, who negotiated the religious politics of the time, from Edward VI, through Mary Tudor, and then Elizabeth I, and so would have conducted services in Latin and English, depending which monarch was on the throne.

Not all the memorials date from Georgian times onward, and in the Chancel is a brass commerating Henry Wilsha, Rector between 1551 and 1592, who negotiated the religious politics of the time, from Edward VI, through Mary Tudor, and then Elizabeth I, and so would have conducted services in Latin and English, depending which monarch was on the throne.

Before we move outside, we must draw your attention to the carved stone reredos above the altar (1873) depicting the wedding at Cana, feeding of the five thousand, and the Ascension. There are also poignant memorials to those fallen in battle, and honoured in our church and a wonderful Victorian memorial carved eagle lectern.

The chu rch clock is a Victorian addition, and thanks to the intervention of Jane Falconer, faces West, for the benefit of the children in the old school (now the village museum). There are 6 bells, 5 dating froEm 1760 and recast in 1978 (though there would have been bells long before these). The 6th was added in 1928 (see the plaque on the wall). Originally there was a raised chamber, accessed by a precarious stairway behind the Tower wall, and you can still see evidence of this.

rch clock is a Victorian addition, and thanks to the intervention of Jane Falconer, faces West, for the benefit of the children in the old school (now the village museum). There are 6 bells, 5 dating froEm 1760 and recast in 1978 (though there would have been bells long before these). The 6th was added in 1928 (see the plaque on the wall). Originally there was a raised chamber, accessed by a precarious stairway behind the Tower wall, and you can still see evidence of this. We are proud of our churchyard, which in the past few years has been a regular recipient of medal awards from Britain in Bloom. A keen group of volunteers manage the churchyard, balancing ecology with tranquility. The original churchyard was extended in 1932, towards the Rectory garden, and again in 1996 (the area furthest from the church with the Sussex style wall)

We are proud of our churchyard, which in the past few years has been a regular recipient of medal awards from Britain in Bloom. A keen group of volunteers manage the churchyard, balancing ecology with tranquility. The original churchyard was extended in 1932, towards the Rectory garden, and again in 1996 (the area furthest from the church with the Sussex style wall)

The photograph shows the glorious early bulb display, with the Rectory in the bacground. This was built in 1934, and the first incumbent was the Rev, Richard Faithfull, last in the line of the 3 Faithfulls who served as Rector from 1860 to WW II . The First rectory, in Greyfriars Lane was used for many centuries up until 1881, and became St. Joseph’s Convent/Abbey.

THE FRANCIS MOND MONUMENT ST MARY’S CHURCH, STORRINGTON, North Aisle, East Wall

Peter Stevens, Treasurer Storrington Museum

Francis Leopold Mond (1895-1918) was the eldest son of Emile Mond, a well-known chemical engineer of his day, and his wife Angela, who lived at Greyfriars, Storrington. Francis was commissioned into 6th Battalion, London Brigade Field Artillery in July 1914 and joined the Royal Flying Corps in February 1915 where he trained as a pilot. He flew on active service in France until invalided home after an accident. In March 1918 he joined 57th Squadron. On May 15th 1918, flying a DH4 bomber with E.M. Martyn, a Canadian observer, they attacked ammunition dumps at Bapaume before themselves being attacked and shot down by German scouting aeroplanes, crashing in No Man’s Land.

Francis Leopold Mond (1895-1918) was the eldest son of Emile Mond, a well-known chemical engineer of his day, and his wife Angela, who lived at Greyfriars, Storrington. Francis was commissioned into 6th Battalion, London Brigade Field Artillery in July 1914 and joined the Royal Flying Corps in February 1915 where he trained as a pilot. He flew on active service in France until invalided home after an accident. In March 1918 he joined 57th Squadron. On May 15th 1918, flying a DH4 bomber with E.M. Martyn, a Canadian observer, they attacked ammunition dumps at Bapaume before themselves being attacked and shot down by German scouting aeroplanes, crashing in No Man’s Land.

Francis is buried in France at Doullens Communal Cemetery Extension No 2 although for four years his family were not aware of this fact. The plane crash had been witnessed by a group of Australian Infantry one of whom, Lieutenant Albert Hill, had volunteered to take a group to rescue the pilot (Mond) and Observer (Lt E M Martyn) while under fire for which he received the Military Cross.

The two bodies were recovered and taken to the HQ after which it seems they were misplaced. Francis’ mother, Angela, carried out an extensive investigation of her own contacting everyone who had been involved however remotely. By 1922, Angela was convinced that two graves in the Doullens cemetery were those of her son and Martyn and not of the men named on the graves. In March 1923, one grave was opened in the presence of Mrs Mond and the father of the man named on the headstone: Captain Aspinall. It was agreed by those present that the body was that of Francis Mond, not Captain Aspinall. The next grave was also opened and the body was established to be that of Lt Martyn, not of the man named. This search for the Francis’ body is a story in itself and is recounted in ‘Missing: The Need for Closure after the Great War’ by Richard van Emden (Pen and Sword).

The Memorial in St Mary’s Church is a tall, impressive, Art Deco style monument consisting of two layers of beige stone with an inset bronze panel, all set on a background of dark grey stone. The memorial is in three parts – the upper portion features a design sculpted in bronze of a female haloed figure holding across both arms a lifeless naked male figure with the word “SACRIFICE”. On either side of the figure are two crosses which suggest war graves. Below the bronze figure is the inscription:

TO THE MEMORY OF CAPTAIN FRANCIS MOND ROYAL FIELD ARTILLERY

AND ROYAL AIR FORCE 57th SQUADRON WHO WAS KILLED FLYING OVER BOUZENCOURT SUR SOMME FRANCE WHILE FIGHTING SEVERAL ENEMY AEROPLANES ON MAY 15th 1918 AGED 22 YEARS.

The third part consists of a partial circle carved in stone, superimposed with a carved eagle, one wing horizontal, one perpendicular and the words ‘PER ARDUA, PER ASTRA’, the motto of the Royal Air Force. The artist’s name, G.R.Hoff, is inscribed on the bottom right of the ledge near the base.

George Rayner Hoff (1894-1937), known as Rayner Hoff, was born in the Isle of Man and served in WW1. In 1923 he moved to Australia after attending the Royal College of Art in London. A world renowned sculptor, he is best known for the sculpted figures forming part of the exterior of the ANZAC Memorial in Hyde Park, Sydney, and the magnificent central group in the interior.

There is a talk ‘Lost and Found: A Monument to Francis Mond by Rayner Hoff’ by Dr Holly Trusted from the V&A Museum on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PPsC0e9CW3A), which is highly recommended.

A selection of more detailed guides can be found in the church and we are indebted to these earlier archivists and recorders for capturing history

It may not feel like it right now, but there are many more chapters to be written in the life of our parish church, as it adapts to meet the needs of worship for the next thousand years, and the current interruption will be but a short paragraph

Martyn Freeman April 2020